It’s one of those long held myths. Having a nightcap, such as brandy or a little

toddy of whisky with hot milk will help

you unwind, and aid sleep.

Wrong.

Alcohol is definitely not good for sleep. It will make you feel sleepy initially and allow you to fall asleep quite

quickly, but it causes you to end up having a poorer quality of sleep, waking more

often and less feeling less refreshed.

And now there is an extra reason to skip the alcohol – it disrupts the important part of your

sleep cycle that is essential for retaining memory.

Having a night on the tiles will, as is commonly known result in a

sore head next morning often with sometimes little recollection of events from

the night before. But even having just

two drinks i.e. within the recommended safe levels of drinking will cut REM sleep as well as deep, slow

wave sleep.

So that’s one myth to dispatch. With many people regularly drinking most nights of the week believing they are doing no harm because they stick to the stipulated recommendations, the reality is that we are unwittingly not only impairing our sleep, but our ability to learn and retain information.

This is of particular concern in a society where regular binge drinking amongst the young, i.e teenagers and young adults is recognised to be a growing problem.

The other thing to consider here is in regards to older brains. Does age really change our

sleep patterns and if so what impact does this have on our brains?

The short answer here is yes, ageing does appear to be associated

with change in sleep patterns.

Doe this matter?

Again the short answer is yes because as with alcohol (which also disrupts

slow wave sleep), it impacts on our ability to remember.

The importance of sleep and cognitive skills is only now really

coming to be better understood.

As we age our sleep pattern starts to change. We may find it

harder to fall asleep, or find we wake more frequently during the night. This has now been found to relate to declining memory function and

loss of brain cells.

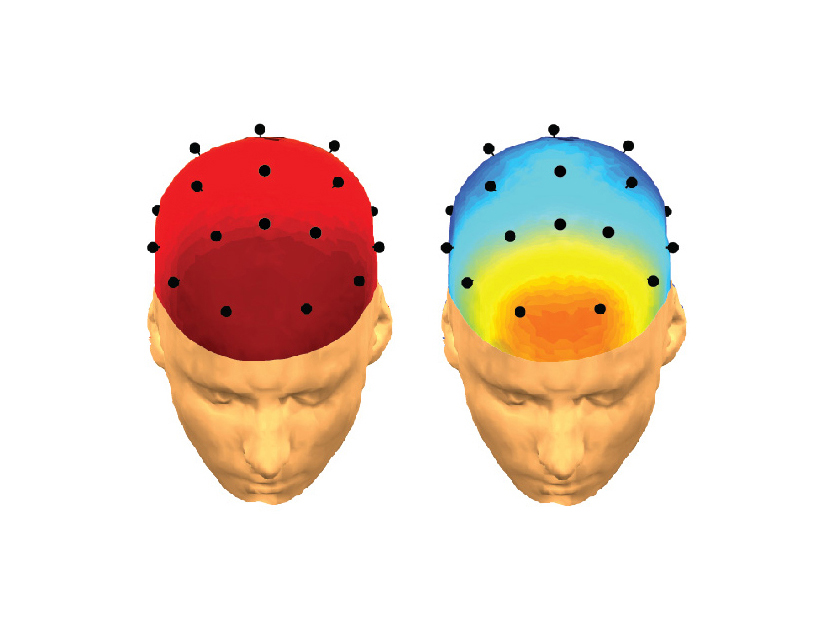

A study at UCLA recruited 33 healthy adults who were either

younger (average age 20) of more mature (average age late 60’s to 70’s)

Each group were asked to memorise a list of word pairs. Ten minutes later they were asked to recall these and then left to

sleep overnight while having an EEG recording taken of their brains. The following morning they were asked to recall the word pairs again

while undergoing brain scans.

So what did

the results show?

Well, perhaps not unexpectedly the older brains performed less

well on the memory tests. What correlated along with this finding was that they

also demonstrated a significant decrease

in the amount of slow brain wave activity associated with deep sleep.

Those with the worst sleep pattern disruption also had the worst

memory performance. In addition these differences were associated with reduction of grey matter (i.e. brain cells) in the part of their frontal lobe called

the medial prefrontal cortex.

This finding suggests that poor

sleep, poor memory and brain deterioration are all interlinked.

Sleep is vital to the process of consolidation of memory. In slow

wave sleep this is the time when it is thought that the transfer occurs of

information from the hippocampus – the area of the brain associated with

learning and memory, to other parts of the brain for long-term storage. In

other words this is the process of embedding memory into our long-term memory

storage banks. If this process is disrupted, we can’t retain the information.

The role of the medial prefrontal cortex here is in regulating the

amount of slow brain wave activity. If brain cells are lost from this area in association with the ageing process,

not only is our sleep pattern altered as a result, but of course it impacts our

ability to form long term memory.

What wasn’t determined from this study (and a factor acknowledged

by the researchers) was the fact that although the older cohort were all

healthy and cognitively intact, so what wasn’t known was the actual state of their

brains from a neurodegenerative point of view. It could be that if they had

early stages of dementia starting to develop this may have produced the effect

on sleep patterns and memory as reported.

This is relevant to consider as sleep disturbance and memory loss are common features associated

with Alzheimer’s disease.

What would be useful here would be to see from future research whether

improving sleep (especially slow brain wave sleep) can help to maintain memory

and long-term memory formation and in addition ward off the clinical symptoms

of Alzheimer’s?

Now that would be worth knowing, to help us ensure we manage our sleep patterns better from an earlier age to retain our cognition for later.

Refs:

Ebrahim, Irshaad O., Shapiro, Colin M., Williams,

Adrian J. and Fenwick, Peter B. (2013) Alcohol and Sleep I: Effects on Normal

Sleep Journal of Alcoholism: Clinical

and Experimental Research doi.org/10.1111/acer.12006

Bryce A Mander, et al (2013)

Prefrontal atrophy,

disrupted NREM slow waves and impaired hippocampal-dependent memory in aging

Nature Neuroscience doi:10.1038/nn.3324

Image:

Bryce Mander Ageing brains show a

weakening in brain waves associated with deep sleep (right) compared with younger adults (left) with consequent

memory impairments.