What causes Alzheimer’s disease and some of the other neurodegenerative disease has been an ongoing mystery. With a rapidly ageing population and increasing numbers of those afflicted by these conditions, scientists around the world have been trying to work out the cause, so that more effective diagnoses and treatments can be developed.

For many years the amyloid hypothesis has been a principle path of investigation. This is because many people with Alzheimer’s disease were found to have very high levels of beta-amyloid in their brains, that had accumulated into the characteristic plaques that are synonymous with the condition. Many proponents of the amyloid hypothesis have taken the view that if the pathway to eliminate this abnormal build up can be found, reducing the amyloid load will prevent the loss of communication between neurons and their eventual destruction. But as David Snowdon’s elegant Nun study showed, not every one who gets Alzheimer’s shows this amyloid accumulation and not everyone with abnormally high levels of amyloid in their brain demonstrates the symptoms associated with Alzheimer’s.

The Tau theory of Alzheimer’s has been the second most prominent idea to be investigated. Tau is a protein that normally helps to stabilise the internal structure of neurons. In Alzheimer’s disease this tau becomes denatured and aggregates into what are called neurofibrillary tangles: the second common hallmark of the disease.

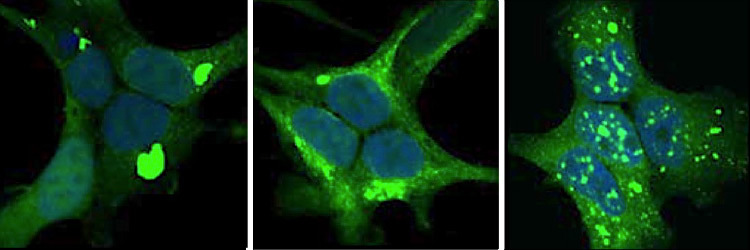

New research from the Marc Diamond lab at Washington University School of Medicine suggests a new theory: that tau can be corrupted in different ways and that these could be linked to 25 distinct forms of damage observed in the brain, called tauopathies.

The Diamond researchers have found that these abnormal forms of tau act like prions. The effects of prions are like bacteria or viruses, though not alive, they can produce a similar effect as when we develop an infection.

The most well known prion disease is “Mad Cow” that became known about in the 1990’s when it was discovered that those cattle affected by the disease, could lead to a similar condition developing in people who consumed the meat from those infected cows.

Prions have also been implicated in the development of Parkinson’s disease and Lou Gehrig’s disease.

How do you treat prion disease?

That’s going to be part of the next step in the investigative process.

Meanwhile, it’s another fascinating piece to fit into the puzzle, expanding our understanding, and hopefully potential effective diagnosis and treatment of some of our most challenging current medical issues.

Ref:

“Distinct tau prion strains propagate in cells and mice and define different tauopathies” by Sanders DW, Kaufman SK, DeVos SL, Sharma AM, Mirbaha H, Li A, Barker SJ, Foley AC, Thorpe JR, Serpell LC, Miller TM, Grinberg LT, Seeley WW, and Diamond ML in Neuron. Published online May 22 2014 doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2014.04.047

Photo credit: Given an opportunity to spread in cells, prion-like proteins taken from the brains of patients with (from top) Alzheimer’s disease, corticobasal degeneration and Pick’s disease form distinctly shaped clumps (green in this image) in different parts of the cells. Credit David W. Sanders.